This month’s HLTH event in Las Vegas provided a fascinating glimpse into the state of healthcare and health technology. The growing shift to both telehealth and value-based care were seemingly everywhere. Nestled squarely within these trends was another hot topic – the growing attention being paid to women’s health, specifically maternal health.

One panel in particular caught my attention: Health Equity, Medicaid and Moms. There is so much to unpack in just the title! In person, it drove a fascinating discussion around the transformation that is happening in this sector and why much more is needed. But walking away from the panel, I felt it also pointed to a glaring gap in the space today – the lack of patient generated data.

The Decline of Women’s Health

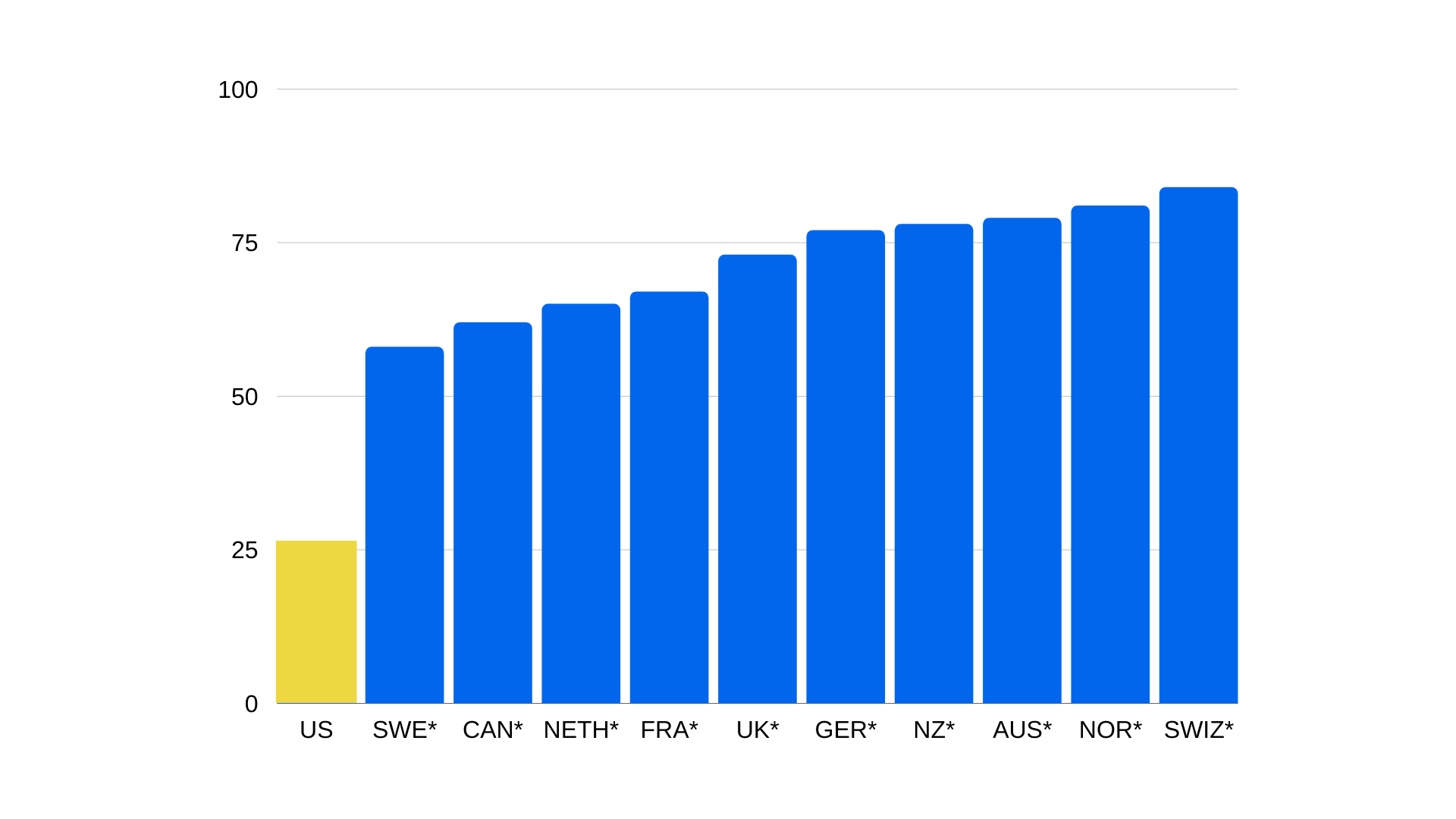

There is no arguing with the fact that women’s health in the United States is severely inadequate. Multiple studies all point to the fact that American women have limited access to lower quality medical care than in comparable countries.

A 2022 Commonwealth Fund report found that more women die from avoidable causes in the United States – including pregnancy – than in other high-income countries. They also have higher rates of multiple chronic conditions, mental health needs and problems paying their medical bills.

Only one-quarter of U.S. women of reproductive age gave a high rating to the performance of their country’s health care system.

These glaring gaps are even worse for maternal health. According to Every Mother Counts, maternal health in this country is going in the wrong direction. Women are now more likely to die from complications of pregnancy and birth than those a generation ago and the number of women dying giving birth has nearly doubled in the last two decades. Black and Indigenous women are up to three times more likely than white women to die from those same complications.

This dire need for improved access to healthcare is one of the driving factors behind the FemTech movement. Encompassing a wide range of technology-enabled solutions, services and companies that address women’s health, the number of startups, funding and deals has grown exponentially in recent years. As a result, the global FemTech market is expected to double to more than $103 billion by 2030.

Patient Insights are Missing

But tech on its own cannot solve America’s shameful lack of support for women’s health and pregnant women. To do that, we need to listen to women and meet them in their lived experiences.

Unfortunately, our healthcare system is ill-equipped to do that because it is not designed to engage proactively or preventively. The traditional fee-for-service approach incentivizes providers to treat symptoms with tests, procedures and pharmaceuticals rather than address root issues or head off complications before they arise.

The lack of support for pregnant women is even more glaring. There is a litany of complications that can arise during pregnancy and – worse – roughly 20% of women of child-bearing years have a pre-existing condition that could impact their pregnancies. So why is it considered best practice for pregnant women to only meet with a doctor every 4-5 weeks until they get closer to birth?

The challenges continue after birth when women are rushed out of the hospital by insurers. The average stay after a normal childbirth in this country is only a day or two. And post-pregnancy doctor appointments are focused on the newborn, not the mother. In fact, the only person looking after the mother is often the mother herself. This is a poor substitute for attentive healthcare and can open the door to a host of physical and mental complications.

PGHD as Industry Standard

What this burgeoning FemTech movement needs is to embrace the role of patient-generated data (PGHD). This concept of capturing first-person perspectives as part of the medical or patient experience is gaining traction in medicine overall, especially in relation to chronic conditions. It is also well-aligned with the broader shift to value-based care in medicine that emphasizes positive patient outcomes.

Engaged providers realize the ability to blend wearable data, journal entries and other PGHD can help fill in the gaps for care teams as they struggle to understand the impact of adherence, externalities or complications on a course of treatment. Given the lack of support for women’s health – specifically expectant and new mothers – in America, the value of PGHD would seem to be obvious.

Anecdotally, this is happening for women using doulas or midwives. They realize the value of the mother’s point of view and ask them to capture observations, insights and concerns in between visits. Regrettably, much of it is being done using paper in physical journals so we don’t get the benefit of recorded data that can be aggregated and shared for broader learnings. But it’s a first step and will hopefully influence broader uptake of the process.

Our ultimate goal should be an established industry practice wherein women and new mothers are able to use wearable devices and remote monitors alongside digital journaling tools in partnership with their primary care providers. In this way, we can equip those tasked with treating women with a greater level of insight that will improve the quality of care and reverse female and maternal health trends in America.